The old saying goes that if you meet one person with autism, you have met one person with autism. This alludes to the fact that people with autism have such a varying set of preferences, interests, strengths, and needs that no two are alike. As a result, the supports people need varies greatly with some not needing any supports and others requiring intensive, round-the-clock services. Regardless of the intensity of supports required, we should all be working towards a society where people with autism are able to access whatever they need without barriers.

Looking at recent advocacy efforts, much of the focus has been on increasing access to insurance-funded applied behavior analysis (ABA) services (Autism Speaks, n.d.). This is understandable given the decades of research and support from independent professionals supporting the efficacy of ABA for teaching new skills and reducing challenging behaviors (Association for Science in Autism Treatment, n.d.). Gaining access to these services has been a godsend for many as individuals were able to start learning critical skills that allowed them to be more successful. However, in many areas of the country, families were able to access ABA services independent of insurance for decades. This is because ABA was provided to children through the public education system when schools identified ABA as necessary for children to access their education.

The overlap between ABA and special education is well established, from the fact that the majority of evidence-based practices identified by professors of special education at the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at UNC Chapel Hill are based in ABA (The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder, n.d.) to leading textbooks on instruction providing attributions to ABA such as “I learned how to teach students with [moderate and severe disabilities] by applying instruction in a systematic fashion based on the principles of ABA” (Collins, 2022, p. XI).

Despite this, access to ABA through a child’s entitlement right of their free appropriate public education (FAPE) as codified in the Individuals with Disabilities Education ACT (IDEA) is not consistent across the United States. Many regions have resisted incorporating ABA into their educational practices for one reason or another. A quick search of legal cases reveals numerous cases where families are seeking special educational services based in ABA. In fact, this was at the heart of the Endrew F. Supreme Court case that looked at what amount of educational progress was necessary for children with autism (Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District, 2017). In that case, the family of a child with autism placed their son in a private school that used ABA as its instructional method after public schools declined to provide ABA services and the child was unable to meet his educational goals. The child quickly began to progress once ABA was used as the educational method. As a result, the Supreme Court agreed with the family that the public school district did not provide Endrew with a FAPE because he did not make meaningful progress there, whereas the private ABA did.

If you talk to families who were at the forefront of advocating for autism insurance, many will tell you that one of the reasons they pushed for insurance-funded ABA was they felt that it would be easier to obtain those services than through the education system. This is understandable as families needed to secure effective services for their children as soon as possible. However, this dominant focus on insurance-funded ABA has created a system where families feel they have to decide between their child receiving ABA through insurance or accessing their education. This has led to the unfortunate practice of families making the difficult decision to un-enroll their children from public schools in order to increase the hours of insurance-funded ABA they receive.

However, insurance-funded ABA is not a replacement for education. There are many critical skills that insurance-funded ABA is prohibited from targeting, such as reading and math skills. This is why if you talk to any insurance-funded ABA provider, they will tell you about the verbal gymnastics they go through to work around these limitations by targeting things like increasing “group responding” and “textual behavior” in order to access funding to teach things like reading without explicitly saying they are teaching reading. Further, many of the benefits and methods families and advocates fought so hard to secure through insurance-funded ABA are entitlements in special education. This includes a focus on increasing adaptive behavior and communication skills, while decreasing challenging behaviors. It also includes the use of evidence-based interventions such as systematic instruction and functional behavior assessments. This is why many states include ABA as a related service in children’s education services.

As such, it is time for the autism community to focus on advocating for a system where families do not have to decide between having their children access their entitlement of an education or insurance-funded ABA. This is a false choice that forces children to sacrifice half of the supports to which their child is entitled. Children should be able to access both. This includes a robust education where they make meaningful progress year over year, and if ABA is the method that facilitates that progress, then schools should provide services based on an ABA framework. Then, those same children should have access to insurance-funded services to support non-school hours.

Creating this system will require a shift in advocacy efforts to a greater focus on ensuring access to children’s federally protected entitlement to FAPE. This will need to be accomplished in a slightly different way than the push for autism insurance because the law guaranteeing children’s educational rights already exists. Therefore, much of the focus will need to be on broader education efforts to inform people of what individuals’ rights are and helping ensure everyone is able to access them. For instance, the simple topic of “meaningful progress,” the term used by the Supreme Court in the Endrew F. case, can be challenging. Because each individual with autism is so unique, it can be a difficult to determine what exactly counts as meaningful for each child. Similarly, the intricacies of state and federal policies can be difficult to navigate. Therefore, a broad based effort to educate everyone about their rights and providing supports to ensuring all children can access those rights is critical at this time.

With that being said, there is also a place for additional legislation in some areas. For instance, schools operate on a fixed budget and many children with autism have more extensive support needs. Therefore, schools often do not have the funding available to supply all the services a child with autism can benefit from. Although federal law prohibits educational teams from considering cost when making decisions (Wettach, 2017, p. 95), the reality is that limited funds does pose significant a barrier for some children. Therefore, advocacy to increase funding for children with more extensive needs could help.

Any shift like this is difficult, as so much has been invested in the fight to increase access to insurance-funded ABA. However, given the many achievements in this area and the unintended consequences that have resulted, this refocus is warranted. This is because doing so is the only way to ensure children with autism are able to access all of the supports they deserve, a robust education with needed services available outside of school. The educational entitlement is something no family should give up for their child. We must do better on behalf of all children.

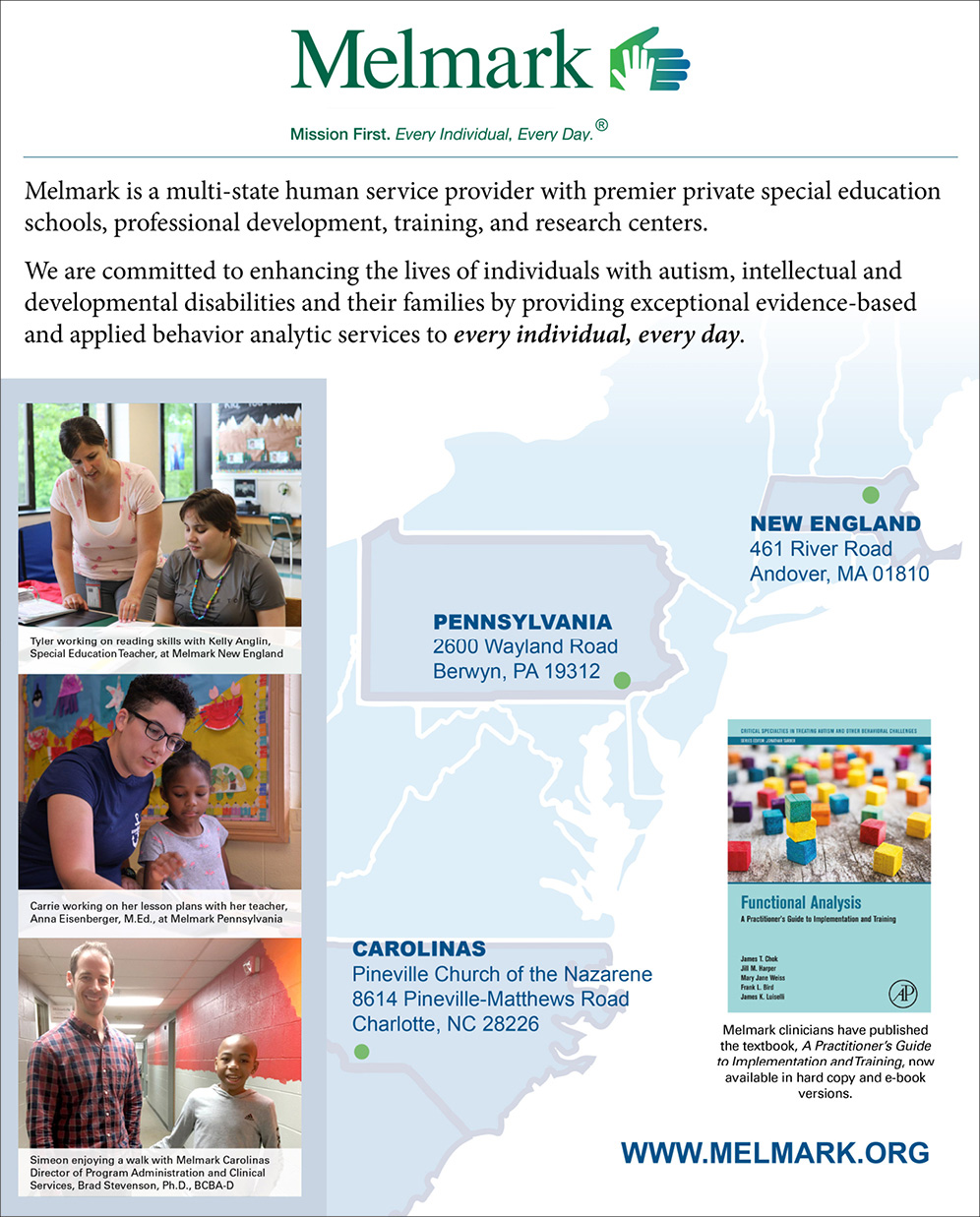

Bradley S. Stevenson, PhD, BCBA-D, is the Director of Program Administration and Clinical Services and Keri Bethune, PhD, BCBA-D, is Director of Educational Services at Melmark Carolinas. Rita M. Gardner, MPH, LABA, BCBA, CDE, is President and CEO of Melmark.

References

Collins, B. C. (2022). Systematic instruction for students with moderate and severe disabilities (2 nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company.

Endrew F. v. Douglas Co. School Dist. Re-1, 137 S. Ct. 988, 580 U.S., 197 L. Ed. 2d 335 (2017).

The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (n.d.). Evidence based practices. https://autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/evidence-based-practices

Wettach, J. R. (2017) A parents’ guide to special education in North Carolina. Children’s Law Clinic, Duke Law School.

Telehealth services enhance care for autism spectrum disorder, offering flexibility, accessibility, and improved multidisciplinary support.

An interdisciplinary approach revolutionizes care for individuals with complex behavioral profiles and medical needs.

The Neuro-Strength-Based Support framework transforms autism interventions by focusing on strengths, neuroscience, and collaboration.

Pioneering value-based care in developmental disability care, Catalight works to improve outcomes, costs, and family wellbeing.

Improve support for autistic individuals using Acceptance Commitment Therapy to embrace sensory sensitivities.