![]()

The central dogma of molecular biology suggests that the primary role of RNA is to convert the information stored in DNA into proteins. In reality, there is much more to the RNA story.

![]()

© 2009 Nature Education All rights reserved.

The central dogma of molecular biology suggests that DNA maintains the information to encode all of our proteins, and that three different types of RNA rather passively convert this code into polypeptides. Specifically, messenger RNA ( mRNA ) carries the protein blueprint from a cell 's DNA to its ribosomes , which are the "machines" that drive protein synthesis. Transfer RNA ( tRNA ) then carries the appropriate amino acids into the ribosome for inclusion in the new protein. Meanwhile, the ribosomes themselves consist largely of ribosomal RNA ( rRNA ) molecules.

However, in the half-century since the structure of DNA was first elaborated, scientists have learned that RNA does much more than simply play a role in protein synthesis. For example, many types of RNA have been found to be catalytic--that is, they carry out biochemical reactions just like enzymes do. Furthermore, many other varieties of RNA have been found to have complex regulatory roles in cells.

Thus, RNA molecules play numerous roles in both normal cellular processes and disease states. Generally, those RNA molecules that do not take the form of mRNA are referred to as noncoding, because they do not encode proteins. The involvement of noncoding mRNAs in many regulatory processes, their abundance, and their diversity of functions has led to the hypothesis that an "RNA world" may have preceded the evolution of DNA and proteins (Gilbert, 1986).

In eukaryotes, noncoding RNA comes in several varieties, most prominently transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA). As previously mentioned, both tRNA and rRNA have long been known to be essential in the translation of mRNA to proteins. For instance, Francis Crick proposed the existence of adaptor RNA molecules that were able to bind to the nucleotide code of mRNA, thereby facilitating the transfer of amino acids to growing polypeptide chains. The work of Hoagland et al. (1958) indeed confirmed that a specific fraction of cellular RNA was covalently bound to amino acids. Later, the fact that rRNA was found to be a structural component of ribosomes suggested that like tRNA, rRNA was also noncoding.

In addition to rRNA and tRNA, a number of other noncoding RNAs exist in eukaryotic cells. These molecules assist in many essential functions, which are still being enumerated and defined. As a group, these RNAs are frequently referred to as small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs), and, in eukaryotes, they have been further classified into a number of subcategories. Together, these various regulatory RNAs exert their effects through a combination of complementary base pairing, complexing with proteins, and their own enzymatic activities.

One important subcategory of small regulatory RNAs consists of the molecules known as small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs). These molecules play a critical role in gene regulation by way of RNA splicing . snRNAs are found in the nucleus and are typically tightly bound to proteins in complexes called snRNPs (small nuclear ribonucleoproteins, sometimes pronounced "snurps"). The most abundant of these molecules are the U1, U2, U5, and U4/U6 particles, which are involved in splicing pre-mRNA to give rise to mature mRNA.

Another topic of intense research interest is that of microRNAs (miRNAs), which are small regulatory RNAs that are approximately 22 to 26 nucleotides in length. The existence of miRNAs and their functions in gene regulation were initially discovered in the nematode C. elegans (Lee et al., 1993; Wightman et al., 1993). Since the time of their discovery, miRNAs have also been found in many other species , including flies, mice, and humans. Several hundred miRNAs have been identified thus far, and many more may exist (He & Hannon, 2004).

miRNAs have been shown to inhibit gene expression by repressing translation. For example, the miRNAs encoded by C. elegans, lin-4 and let-7, bind to the 3' untranslated region of their target mRNAs, preventing functional proteins from being produced during certain stages of larval development . Most miRNAs studied thus far appear to control gene expression by binding to target mRNAs through imperfect base pairing and subsequent inhibition of translation, although some exceptions have been noted.

Additional studies indicate that miRNAs also play significant roles in cancer and other diseases. For example, the species miR-155 is enriched in B cells derived from Burkitt's lymphoma, and its sequence also correlates with a known chromosomal translocation (exchange of DNA between chromosomes).

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are yet another class of small RNAs. Although these molecules are only 21 to 25 base pairs in length, they also work to inhibit gene expression. Specifically, one strand of a double-stranded siRNA molecule can be incorporated into a complex called RISC. This RNA-containing complex can then inhibit transcription of an mRNA molecule that has a sequence complementary to its RNA component.

siRNAs were first defined by their participation in RNA interference (RNAi). They may have evolved as a defense mechanism against double-stranded RNA viruses. siRNAs are derived from longer transcripts in a process similar to that by which miRNAs are derived, and processing of both types of RNA involves the same enzyme , Dicer (Figure 1). The two classes appear to be distinguished by their mechanisms of repression, but exceptions have been found in which siRNAs exhibit behavior more typical of miRNAs, and vice versa (He & Hannon, 2004).

Inside the eukaryotic nucleus, the nucleolus is the structure where rRNA processing and ribosomal assembly take place. Molecules called small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) were isolated from nucleolar extracts because of their abundance in this structure. These molecules function to process rRNA molecules, often resulting in the methylation and pseudouridylation of specific nucleosides. These modifications are mediated by one of two classes of snoRNAs: the C/D box or H/ACA box families, which generally mediate the addition of methyl groups or the isomerization of uradine in immature rRNA molecules, respectively.

Eukaryotes have not cornered the market on noncoding RNAs with specific regulatory functions, however: Bacteria also possess a class of small regulatory RNAs. Bacterial sRNAs are involved in processes ranging from virulence to the transition from growth to the stationary phase, which occurs when a bacterium encounters a situation such as nutrient deprivation.

One example of a bacterial sRNA is the 6S RNA found within Escherichia coli; this molecule has been well characterized, with its initial sequencing occurring in 1980. 6S RNA is conserved across many bacterial species, indicating its important role in gene regulation. This RNA has been shown to affect the activity of RNA polymerase (RNAP), the molecule that transcribes messenger RNA from DNA. 6S RNA inhibits this activity by binding to a subunit of the polymerase that stimulates transcription during growth. Through this mechanism, 6S RNA inhibits the expression of genes that drive active growth and helps cells enter a stationary phase (Jabri, 2005).

Gene regulation in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes is also affected by RNA regulatory elements, called riboswitches (or RNA switches). Riboswitches are RNA sensors that detect and respond to environmental or metabolic cues and affect gene expression accordingly.

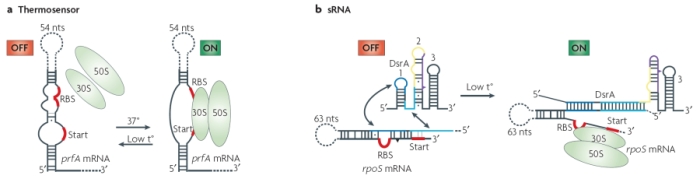

A simple example of this group is the RNA thermosensor found in the virulence genes of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. When this bacterium invades a host, the elevated temperature inside the host's body melts the secondary structure of a segment in the 5' untranslated region of the mRNA produced by the bacterial prfA gene. As a result of this alteration in secondary structure, a ribosome-binding site is exposed, and translation of protein can take place (Figure 2). Additional riboswitches have been shown to respond to heat and cold shocks in a variety of organisms, as well as to regulate synthesis of metabolites such as sugars and amino acids (Serganov & Patel, 2007). It is important to note that, although riboswitches seem to be more prevalent in prokaryotes, many have also been found in eukaryotic cells.

![]()

A) Modified with permission from © 2002 Elsevier. Johansson, J. et al. An RNA thermosensor controls expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell 110, 551–561 (2002). All rights reserved. B) Modified with permission from © 2000 National Academy of Scineces, USA. Altuvia, S. & Wagner, E. G. H. Switching on and off with RNA. PNAS 97, 9824-9826 (2000). All rights reserved.