For many R users, it’s obvious why you’d want to use R with big data, but not so obvious how. In fact, many people (wrongly) believe that R just doesn’t work very well for big data.

In this article, I’ll share three strategies for thinking about how to use big data in R, as well as some examples of how to execute each of them.

By default R runs only on data that can fit into your computer’s memory. Hardware advances have made this less of a problem for many users since these days, most laptops come with at least 4-8Gb of memory, and you can get instances on any major cloud provider with terabytes of RAM. But this is still a real problem for almost any data set that could really be called big data.

The fact that R runs on in-memory data is the biggest issue that you face when trying to use Big Data in R. The data has to fit into the RAM on your machine, and it’s not even 1:1. Because you’re actually doing something with the data, a good rule of thumb is that your machine needs 2-3x the RAM of the size of your data.

An other big issue for doing Big Data work in R is that data transfer speeds are extremely slow relative to the time it takes to actually do data processing once the data has transferred. For example, the time it takes to make a call over the internet from San Francisco to New York City takes over 4 times longer than reading from a standard hard drive and over 200 times longer than reading from a solid state hard drive. 1 This is an especially big problem early in developing a model or analytical project, when data might have to be pulled repeatedly.

Nevertheless, there are effective methods for working with big data in R. In this post, I’ll share three strategies. And, it important to note that these strategies aren’t mutually exclusive – they can be combined as you see fit!

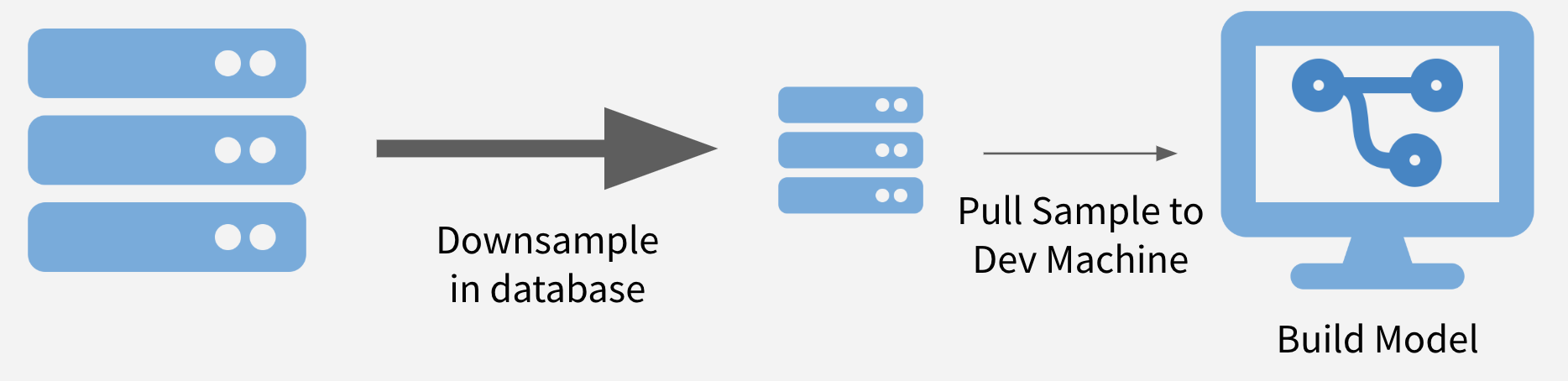

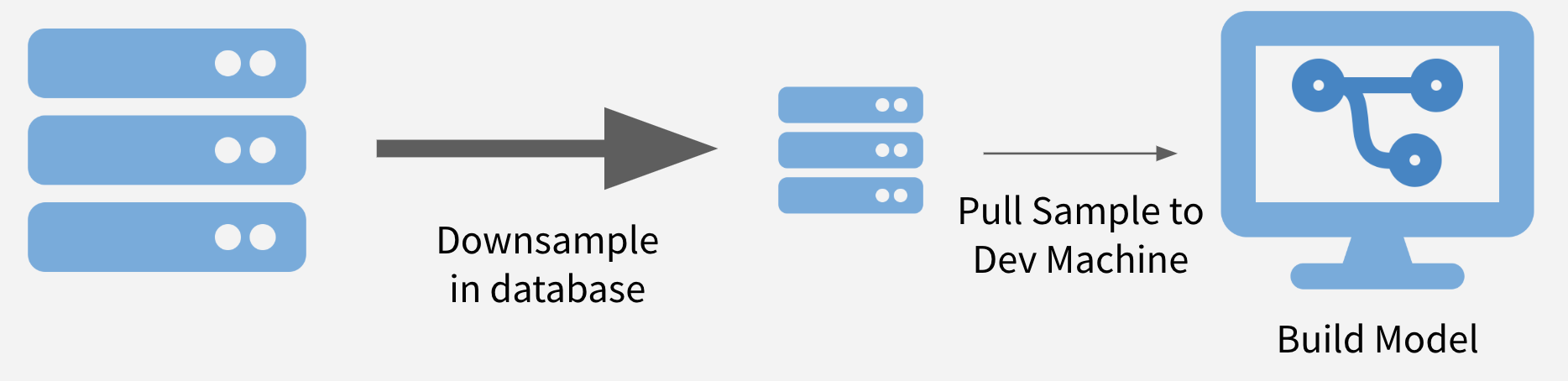

To sample and model, you downsample your data to a size that can be easily downloaded in its entirety and create a model on the sample. Downsampling to thousands – or even hundreds of thousands – of data points can make model runtimes feasible while also maintaining statistical validity. 2

If maintaining class balance is necessary (or one class needs to be over/under-sampled), it’s reasonably simple stratify the data set during sampling.

Illustration of Sample and Model

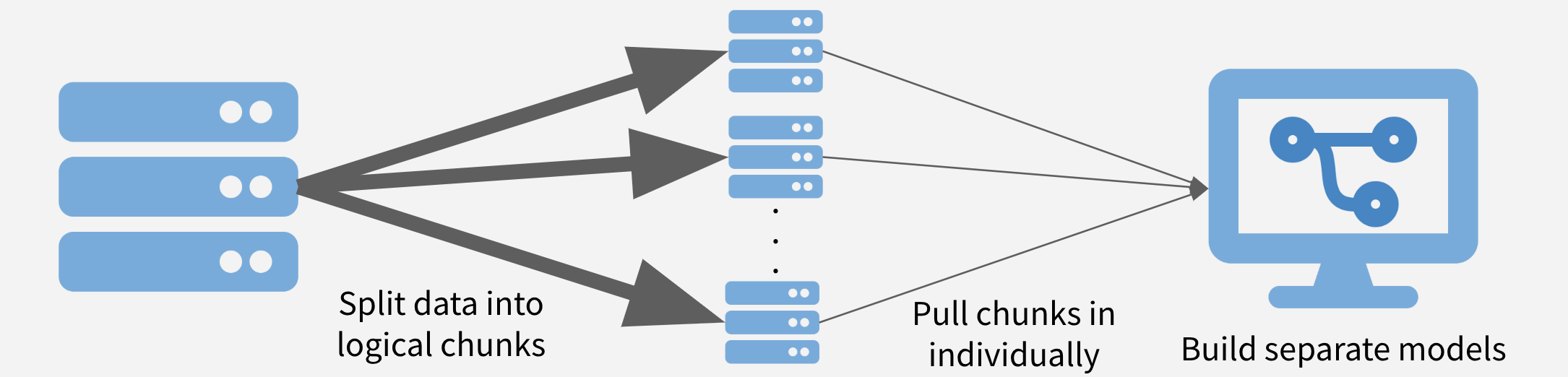

In this strategy, the data is chunked into separable units and each chunk is pulled separately and operated on serially, in parallel, or after recombining. This strategy is conceptually similar to the MapReduce algorithm. Depending on the task at hand, the chunks might be time periods, geographic units, or logical like separate businesses, departments, products, or customer segments.

Chunk and Pull Illustration

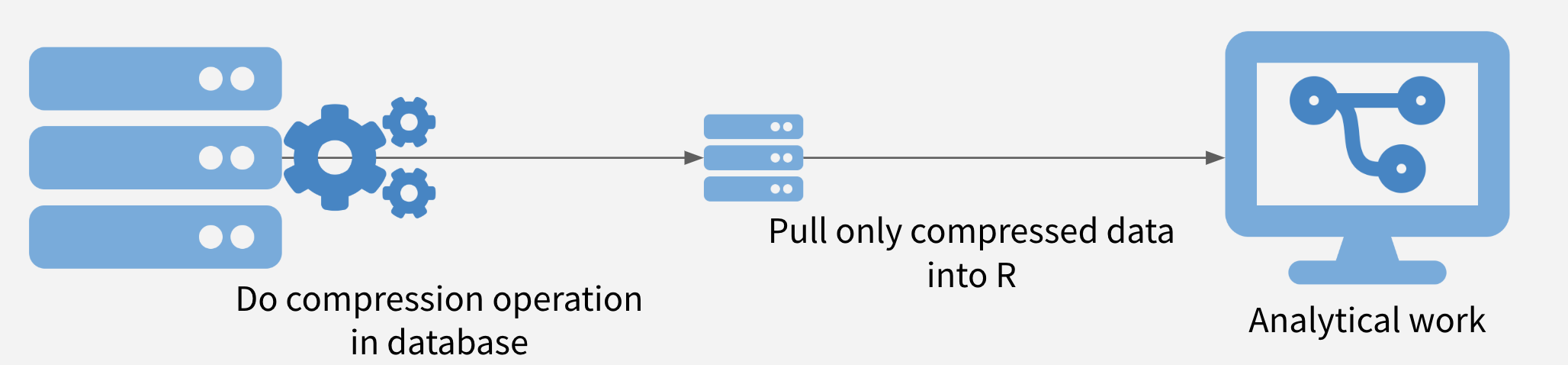

In this strategy, the data is compressed on the database, and only the compressed data set is moved out of the database into R. It is often possible to obtain significant speedups simply by doing summarization or filtering in the database before pulling the data into R.

Sometimes, more complex operations are also possible, including computing histogram and raster maps with dbplot , building a model with modeldb , and generating predictions from machine learning models with tidypredict .

Push Compute to Data Illustration

I’ve preloaded the flights data set from the nycflights13 package into a PostgreSQL database, which I’ll use for these examples.

Let’s start by connecting to the database. I’m using a config file here to connect to the database, one of RStudio’s recommended database connection methods:

library(DBI) library(dplyr) library(ggplot2) db The dplyr package is a great tool for interacting with databases, since I can write normal R code that is translated into SQL on the backend. I could also use the DBI package to send queries directly, or a SQL chunk in the R Markdown document.

## # A tibble: 1 x 1 ## n ## ## 1 336776With only a few hundred thousand rows, this example isn’t close to the kind of big data that really requires a Big Data strategy, but it’s rich enough to demonstrate on.

Let’s say I want to model whether flights will be delayed or not. This is a great problem to sample and model.

Let’s start with some minor cleaning of the data

# Create is_delayed column in database df % mutate( # Create is_delayed column is_delayed = arr_delay > 0, # Get just hour (currently formatted so 6 pm = 1800) hour = sched_dep_time / 100 ) %>% # Remove small carriers that make modeling difficult filter(!is.na(is_delayed) & !carrier %in% c("OO", "HA")) df %>% count(is_delayed)## # A tibble: 2 x 2 ## is_delayed n ## ## 1 FALSE 194078 ## 2 TRUE 132897These classes are reasonably well balanced, but since I’m going to be using logistic regression, I’m going to load a perfectly balanced sample of 40,000 data points.

For most databases, random sampling methods don’t work super smoothly with R, so I can’t use dplyr::sample_n or dplyr::sample_frac . I’ll have to be a little more manual.

set.seed(1028) # Create a modeling dataset df_mod % # Within each class group_by(is_delayed) %>% # Assign random rank (using random and row_number from postgres) mutate(x = random() %>% row_number()) %>% ungroup() # Take first 20K for each class for training set df_train % filter(x % collect() # Take next 5K for test set df_test % filter(x > 20000 & x % collect() # Double check I sampled right count(df_train, is_delayed) count(df_test, is_delayed)## # A tibble: 2 x 2 ## is_delayed n ## ## 1 FALSE 20000 ## 2 TRUE 20000## # A tibble: 2 x 2 ## is_delayed n ## ## 1 FALSE 5000 ## 2 TRUE 5000Now let’s build a model – let’s see if we can predict whether there will be a delay or not by the combination of the carrier, the month of the flight, and the time of day of the flight.

## Area under the curve: 0.6425As you can see, this is not a great model and any modelers reading this will have many ideas of how to improve what I’ve done. But that wasn’t the point!

I built a model on a small subset of a big data set. Including sampling time, this took my laptop less than 10 seconds to run, making it easy to iterate quickly as I want to improve the model. After I’m happy with this model, I could pull down a larger sample or even the entire data set if it’s feasible, or do something with the model from the sample.

In this case, I want to build another model of on-time arrival, but I want to do it per-carrier. This is exactly the kind of use case that’s ideal for chunk and pull. I’m going to separately pull the data in by carrier and run the model on each carrier’s data.

I’m going to start by just getting the complete list of the carriers.

# Get all unique carriers carriers % select(carrier) %>% distinct() %>% pull(carrier)Now, I’ll write a function that

carrier_model % dplyr::filter(carrier == carrier_name) %>% collect() # Split into training and test split % rsample::initial_split(prop = 0.9, strata = "is_delayed") %>% suppressMessages() # Get training data df_train % rsample::training() # Train model mod <- glm(is_delayed ~ as.character(month) + poly(sched_dep_time, 3), family = "binomial", data = df_train) # Get out-of-sample AUROC df_test % rsample::testing() df_test$pred

Now, I’m going to actually run the carrier model function across each of the carriers. This code runs pretty quickly, and so I don’t think the overhead of parallelization would be worth it. But if I wanted to, I would replace the lapply call below with a parallel backend. 3

set.seed(98765) mods % suppressMessages() names(mods) Let’s look at the results.

mods## $UA ## Area under the curve: 0.6408 ## ## $AA ## Area under the curve: 0.6041 ## ## $B6 ## Area under the curve: 0.6475 ## ## $DL ## Area under the curve: 0.6162 ## ## $EV ## Area under the curve: 0.6419 ## ## $MQ ## Area under the curve: 0.5973 ## ## $US ## Area under the curve: 0.6096 ## ## $WN ## Area under the curve: 0.6968 ## ## $VX ## Area under the curve: 0.6969 ## ## $FL ## Area under the curve: 0.6347 ## ## $AS ## Area under the curve: 0.6906 ## ## $`9E` ## Area under the curve: 0.6071 ## ## $F9 ## Area under the curve: 0.625 ## ## $YV ## Area under the curve: 0.7029So these models (again) are a little better than random chance. The point was that we utilized the chunk and pull strategy to pull the data separately by logical units and building a model on each chunk.

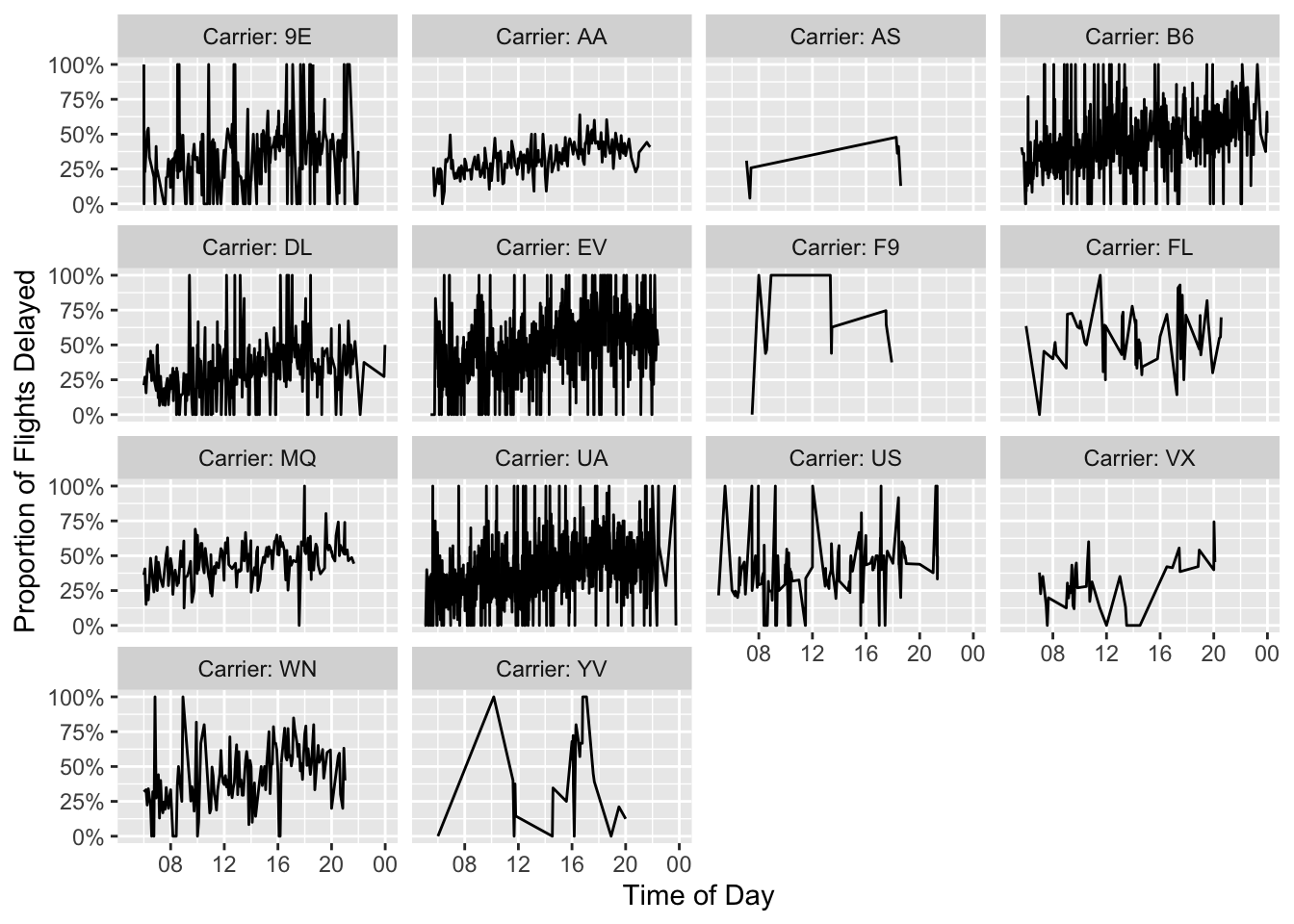

In this case, I’m doing a pretty simple BI task - plotting the proportion of flights that are late by the hour of departure and the airline.

Just by way of comparison, let’s run this first the naive way – pulling all the data to my system and then doing my data manipulation to plot.

system.time( df_plot % collect() %>% # Change is_delayed to numeric mutate(is_delayed = ifelse(is_delayed, 1, 0)) %>% group_by(carrier, sched_dep_time) %>% # Get proportion per carrier-time summarize(delay_pct = mean(is_delayed, na.rm = TRUE)) %>% ungroup() %>% # Change string times into actual times mutate(sched_dep_time = stringr::str_pad(sched_dep_time, 4, "left", "0") %>% strptime("%H%M") %>% as.POSIXct())) -> timing1Now that wasn’t too bad, just 2.366 seconds on my laptop.

But let’s see how much of a speedup we can get from chunk and pull. The conceptual change here is significant - I’m doing as much work as possible on the Postgres server now instead of locally. But using dplyr means that the code change is minimal. The only difference in the code is that the collect call got moved down by a few lines (to below ungroup() ).

system.time( df_plot % # Change is_delayed to numeric mutate(is_delayed = ifelse(is_delayed, 1, 0)) %>% group_by(carrier, sched_dep_time) %>% # Get proportion per carrier-time summarize(delay_pct = mean(is_delayed, na.rm = TRUE)) %>% ungroup() %>% collect() %>% # Change string times into actual times mutate(sched_dep_time = stringr::str_pad(sched_dep_time, 4, "left", "0") %>% strptime("%H%M") %>% as.POSIXct())) -> timing2It might have taken you the same time to read this code as the last chunk, but this took only 0.269 seconds to run, almost an order of magnitude faster! 4 That’s pretty good for just moving one line of code.

Now that we’ve done a speed comparison, we can create the nice plot we all came for.

df_plot %>% mutate(carrier = paste0("Carrier: ", carrier)) %>% ggplot(aes(x = sched_dep_time, y = delay_pct)) + geom_line() + facet_wrap("carrier") + ylab("Proportion of Flights Delayed") + xlab("Time of Day") + scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent) + scale_x_datetime(date_breaks = "4 hours", date_labels = "%H")

It looks to me like flights later in the day might be a little more likely to experience delays, but that’s a question for another blog post.

You may leave a comment below or discuss the post in the forum community.rstudio.com.